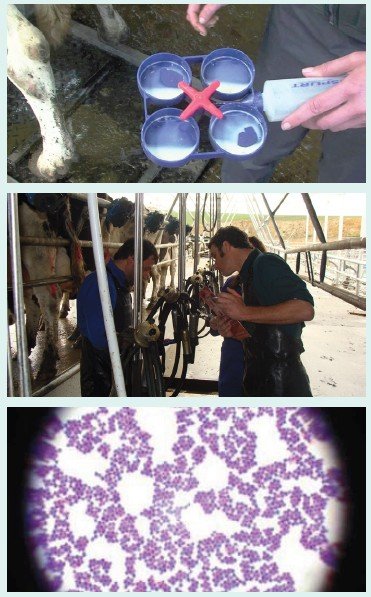

Mastitis Multiplex PCR – A big advance in milk quality management

/Many of you will be aware of the highly convenient, Staph aureus PCR test that LIC has had an available for use on herd test samples for the last 10 years.

This season the test has got better. As well as a much improved sensitivity (improved chance of detecting Staph aureus if the cow is infected with it), the test will also simultaneously detect Strep uberis, Strep dysgalactia and will look for the presence of the BLAZ gene.

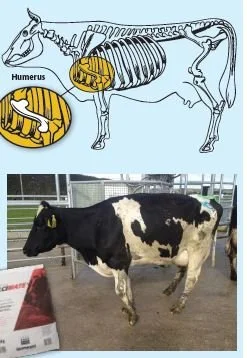

Cows detected with Staph aureus can be managed separately over the season to minimise spread to other cows. At the end of the season, these cows may be considered for culling (particularly if they possess the BLAZ gene, have been chronically high SCC or are greater than 6-7 years old.

The finding of either Strep species at a high incidence provides some certainty of the main cause of high somatic cell count cows and gives a greater confidence in the retention of younger infected cows when treated with DCAT as cure rates should be high.

The BLAZ gene is found in bacteria that are resistant to beta lactam antibiotics - e.g. penicillin. Cow milk found to contain this gene have bacteria on board which are less likely to cure with antibiotics and pose a risk to the development of herd level antibiotic resistance. Cows with Staph aureus and the BLAZ gene should definitely not be retained.

Testing of herd test samples must be booked with LIC in advance via our vet clinic. Talk to your Prime Vet. Once the herd test results are through, your Prime Vet will screen the HSSC cows and select those for testing. Typically these will be cows that are chronically high or with a SCC over 250-400,000 at the most recent herd test.

Cost of testing is $19 per cow (excluding GST). This is very good value. A minimum of 25 cows must be sampled.